Economic liberalization: A case study using synthetic and generalized synthetic control methods

- Ethan Lobdell

- Nov 15, 2021

- 9 min read

Research Problem

Broadly, this research proposal seeks to explore the impact economic crises and economic liberalization has on a nation's long-term economic growth. Specifically this paper seeks to explore the effect India’s 1991 economic crisis and trade liberalization reforms had on GDP growth. Synthetic control methods will be used to construct and compare counterfactual estimates of India’s GDP outcome had the crisis not occurred.

Background

In 1991, India experienced a severe economic crisis due to significant trade imbalances and a fiscal policy that nearly resulted in the Indian government defaulting on its financial obligations, with barely enough capital reserves to pay for three weeks of basic goods. Joshi & Little (1994) called the 1991 crisis a “policy-induced crisis par excellence", due to a failure in macroeconomic policies resulting in inflation above 10 percent, trade deficits, heavy foreign debt, and isolation from additional foreign lending instruments. The crisis was distinguished by a sharp depreciation in their currency, the rupee. In response to the crisis, a new political leadership was elected and trade policies were slowly liberalized to allow more foreign investments to boost their economy.

Significance

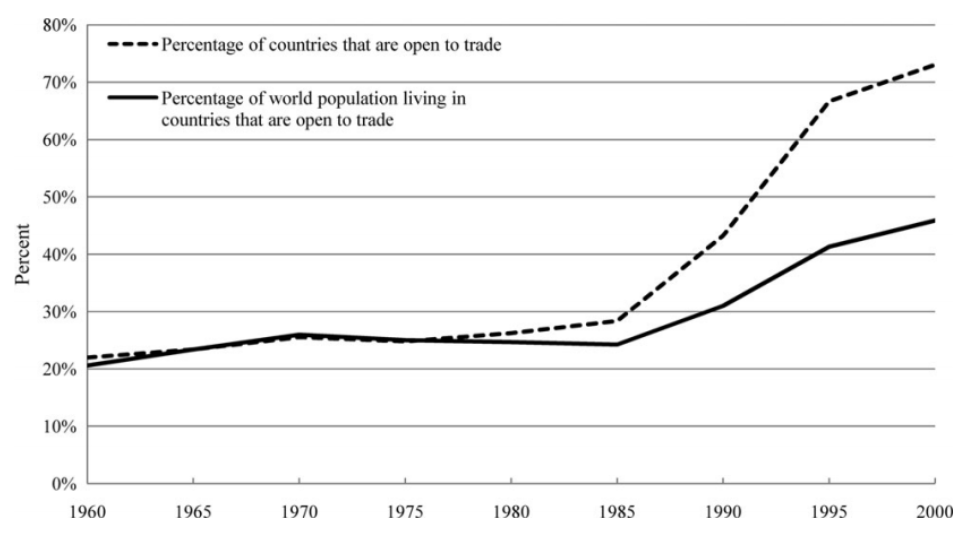

Economic liberalization encompasses government policies that promote free trade, deregulation, elimination of subsidies, price controls and rationing systems, and often the privatization of public services. With the argument being that market oriented policies will lead to economic growth (United Nations, 2010). In Figure 1 (Wacziarg & Welch, 2008) we see a dramatic escalation from ~20%(1980) to ~72% (2000) of countries that are classified as liberalized and open to trade. Wacziarg & Welch (2008) note that the primary reason the percentage of the world population living under liberalized trade is significantly less than the percent of liberalized countries is that both China and India were not classified as open liberalized economies.

Figure 1. Openness to Trade, 1960-2000 Note: Openness is defined according to the Sachs and Warner (1995) criteria. Sample includes 141 countries. Figure Source: (Wacziarg & Welch, 2008)

Between 1991 and 2019, the Indian GDP rose from $266 billion to $3 trillion. Economic liberalization is practically and theoretically dominant on a global scale and India’s status as the 2nd largest nation and 6th largest economy, signals the importance of this research.

Literature Review

In exploring the literature of the causal effect associated with economic liberalization on economic outcomes, Billmeier & Nannicini (2013) used synthetic control methods (SCM) (Abadie, Diamond, & Hainmueller, 2015) to compare actual per capita GDP outcomes against the counterfactual case of a treatment unit having not crossed the economic liberalization threshold. They used a binary indicator to assign whether a country was considered “liberalized” via a formula derived by Sachs & Warner (1995) and revised by Wacziarg & Welch (2008). Billmeier & Nannicini (2013) followed the Wacziarg & Welch (2008) determination that India was not liberalized and hence not a case for treatment analysis using the SCM. Wacziarg & Welch (2008) had refined and in principle corrected Sachs & Warner (1995) who had designated India as liberalized starting in 1994.

The designation conflict between Sachs & Warner (1995) and Wacziarg & Welch (2008) opens the space to either explore the thresholds for designation or perhaps more simply, to compare actual outcomes against counterfactual outcomes constructed from clear donor pools of both open and closed countries.

Sachs & Warner (1995) also remark that no conflict was present in India despite the overwhelming literature that claims the opposite, that the events of 1991 constituted a significant economic crisis (Ahluwalia, 2002; Cerra & Saxena, 2002; Ghosh, 2006; Panagariya, 2020). And, while we could again refine the designation criteria, this proposal assumes that a “crisis” had occurred. Regardless, through the use of both the GSC and SCM, this proposal can incorporate both conclusions, where the synthetic control uses the simpler assumption that a crisis event occurred and that designates exposure to treatment or not. Whereas the generalized synthetic control method assumes no crisis occurred and the analysis can focus on the gradual reform implementations that perhaps are more causally related to the outcomes compared to the crisis itself (Sachs & Warner, 1995; Wacziarg & Welch, 2008).

From the perspective of liberalizing reforms, the dominant narrative is that those reforms began in 1991 in response to the currency crisis (Joshi & Little, 1996). Yet, there appears to be considerable debate that the reforms had already begun in the early 1980’s. And still yet, India’s designation as a liberalized nation was not academically recognized until at least 10 years after 1991 (Wacziarg & Welch, 2008). The debate not only seems to hinge on the date that reforms began and when designation was official, but also and perhaps more importantly, whether liberalization itself is causally related to the growth in GDP. First, Panagariya (2020) argues that the growth rates in the 1990’s were not significantly dissimilar from those in the 1980’s and hence contests the assumption that liberalization efforts are causally responsible for GDP growth. But, Kotwal et al. (2011) clarifies and partially refutes Panagariya’s (2020) critique of liberalism's impact by concluding that liberalism was responsible for sustaining the 1980’s growth rate into the 1990’s that would have otherwise plummeted and hence relative to zero or negative growth, sustained growth is a significant impact.

The findings of Kotwal et al. (2011) further motivates the need for this research proposal by concluding that the significance of liberalization measures can be evaluated by “imagining the counterfactual that India had stayed in its prereform state”. A seemingly bold conclusion to compel the reader to “imagine”, given the title of their paper “Economic Liberalization and Indian Economic Growth: What’s the Evidence?” hints at an evidence based approach to counterfactual cases, not imaginary ones.

Methods

This research proposal is a retrospective case-control study of the causal effect associated with currency crises resulting in economic liberalization reforms.To effectively explore a potential causal effect, I choose to apply both the synthetic (Abadie et al., 2015) and generalized synthetic control methods (Xu, 2017) to define counterfactual synthetic control units to quantitatively estimate the true causal effect of the 1991 economic crisis on GDP over the subsequent 6-10 years.

Both methods utilize a donor pool of aggregate units (countries) that share similar characteristics of India yet are not exposed to a crisis. In the case of India in 1991, the metric for defining a crisis was a sharp depreciation in their national currency, the rupee (Cerra & Saxena, 2002). This paper will construct two unique donor pools that will be used to address the discrepancies identified in the literature about when India is officially considered liberalized and what effect the crisis and reforms may have had on GDP.

In constructing the control unit donor pool(s), this proposal seeks countries whose covariates straddle those of India’s and lack a currency crisis event over the pre-treatment and post-treatment periods. Each donor pool will be constructed of nations whose liberalization status, as defined by Wacziarg & Welch (2008), is either liberalized (1) or closed (0). This will allow us to construct two counterfactuals for India. One based upon a donor pool of liberalized nations and one based upon a donor pool of closed nations.

The two donor pools will both be constructed of a convex hull of covariate values that straddle India’s covariate values and optimally have the potential to extend post-treatment estimates beyond the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, should those units not have been affected. This proposal will mirror the Billmeier & Nannicini (2013) approach who themselves used the seminal work of Barro (1991) to collect data on the following covariates: average population growth, secondary school enrollment, investment share, inflation, and democratic status.

One of the key requirements for an effective SCM is that there is sufficient pre-treatment data to both construct and validate the synthetic control unit to provide greater confidence in the post-treatment estimates. Second is that there are no systemic shocks to control units within the donor pool that could impact the outcome of interest (Abadie et al., 2015). Given there was a financial crisis across most of Asia in 1997, I acknowledge that most potential regionally similar control units will only have about 6 years of post-treatment data if their GDP’s were confounded by that crisis (Radelet & Sachs, 1998).

The generalized synthetic control method (GSC) will provide diagnostic validation through its ability to incorporate variable treatment periods (Xu, 2017). This functionality will be utilized to address two issues in this proposal. One, it will allow this analysis to extend post-treatment periods beyond the 1997 Asian financial crisis by incorporating a secondary treatment shock into the model and two, it will also allow for the analysis to explore the impact of gradual liberalization reforms (Ahluwalia, 2002). This second application of the GSC will address the debate that there was no crisis event by instead exploring the gradual liberalization reforms effect on India’s GDP. This second exploration relaxes the assumption that the economic crisis was responsible for GDP effects and instead will allow the analysis to focus on the reforms themselves, which despite their gradual nature, may be more causally responsible for changes in GDP.

The above two methods will provide insight into the effect that the crisis and liberalization reforms may have had on India's GDP.

Expected Results

This proposal is interested in observing how the counterfactual GDP estimates generated by the donor pool of liberalized nations and the donor pool of closed nations compare to India’s actual GDP. This proposal seeks to quantify the gap between India’s actual GDP and the two counterfactual GDPs to evaluate several hypotheses.

Based upon the current literature, the economic reforms post 1991 were partially responsible for India’s GDP growth and so this proposal predicts that the counterfactual of a closed India will predict a GDP that builds up over time albeit less so than actual India’s GDP growth because the lack liberalization policies limited capital flow into the counterfactual Indian economy. Second, this paper predicts that the counterfactual of an open India will estimate a positive GDP effect over actual India, because the gradualist reforms of actual India diminished the potential actual growth, had they been fully open (Kotwal et al., 2011). From Figure 2, we see India’s actual GDP growth between 1980 and 2005 straddled by the hypothetical counterfactual closed and open Indias that diverged at the year 1991 when the crisis event occurred.

Figure 2: India’s GDP, and hypothetical counterfactual GDP for a closed and open India in Billions of US dollars between 1980 and 2005. Data Source: (Macrotrends, 2020)

The counterfactual trajectories of both open and closed India will provide novel insight into the effect of the 1991 crisis, the gradualist reforms, and the designation of liberalized or not. If actual India is closer to the trajectory of the closed donor pool, this would support the designation by Wacziarg & Welch (2008) or refute it if India was closer to the open trajectory donor pool. Secondarily if either counterfactual trajectories don’t diverge at the 1991 date, we will evidence that the crisis itself was not strongly related to the GDP outcomes and this lends more support to the gradualist reform hypothesis. Lastly, if upon running the GSC we observe a distinct positive effect between models that include and omit trade reforms, then we will have evidence that the reforms, albeit gradual, still overall positively affected the GDP.

These outcomes of how counterfactual estimates of India’s GDP compared to actual India’s GDP growth during the 1990’s will be an important contribution to the current literature, given they won’t be based in researchers “imaginations” but in the evidence. While Kraev (2005) did explore the counterfactual histories of trade liberalization and GDP effects for developing nations by regression methods, he did so in aggregate, not focusing on India nor utilizing synthetic control methods. There was no obvious example that I could find of a counterfactual causal study of the 1991 currency crisis to estimate India’s alternative history had the crisis or liberalization reforms not taken place. Therefore a justified quantitative alternative GDP history will help answer the important question about how the 1991 Indian currency crisis and resulting liberalization reforms affected India’s GDP.

Conclusion

India is the second largest nation with the sixth largest GDP in the world. And while economic liberalization is the most dominant economic theory and policy driver globally, some national economies are still partially closed. The results of this work could certainly inform liberalization reforms in those nations. Exploring India’s reform history from a closed economy to a more open one and its subsequent GDP outcomes is a useful case study in broadly understanding the liberalization process and how it affects GDP. The synthetic control method is a key new statistical tool, yet to be employed in this context, to recreate alternative histories to better understand the effects associated with crisis events and policy reforms. Gaps in the literature, India’s size and important role in the global economy compel us to further clarify how the 1991 currency crisis and subsequent trade liberalization reforms influenced their long-term GDP trajectory.

References

Abadie, A., Diamond, A., and Hainmueller, J. (2015). Comparative politics and the synthetic control method. American Journal of Political Science, 59(2), 495-510.

Abadie, A. (2019). Using synthetic controls: Feasibility, data requirements, and methodological aspects. Journal of Economic Literature.

Ahluwalia, Montek, S. 2002. "Economic Reforms in India Since 1991: Has Gradualism Worked?" Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16 (3): 67-88.

Barro, R. J., “Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 106 (1991), 407–443

Billmeier, A., and Nannicini, T. (2013). Assessing economic liberalization episodes: A synthetic control approach. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(3), 983-1001.

Cerra, V., and Saxena, S. C. (2002). What caused the 1991 currency crisis in India?. IMF staff papers, 49(3), 395-425.

Ghosh, A. (2006). Pathways Through Financial Crisis: India. Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, 12(4), 413–429. https://doi.org/10.1163/19426720-01204006

Joshi, V., and Little, I. M. D. (1994). India: Macroeconomics and political economy, 1964-1991. The World Bank.

Joshi, V., & Little, I. D. (1996). India's economic reforms, 1991-2001. OUP Catalogue.

Kotwal, Ashok, Bharat Ramaswami, and Wilima Wadhwa. (2011). "Economic Liberalization and Indian Economic Growth: What's the Evidence?" Journal of Economic Literature, 49 (4): 1152-99.

Kraev, E. (2005). Estimating GDP Effects of Trade Liberalization on Developing Countries. Christian Aid, London.

Macrotrends. (2020). India GDP 1960-2020. https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/IND/india/gdp-gross-domestic-product

Nuruzzaman, M. (2005). Economic liberalization and poverty in the developing countries. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 35(1), 109-127.

Panagariya, A. (2005). India in the 1980s and the 1990s: A Triumph of Reforms. In India’s and China’s recent experience

with reform and growth (pp. 170-200). Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Radelet, S., and Sachs, J. (1998). The onset of the East Asian financial crisis (No. w6680). National bureau of economic research.

Sachs, J. D., Warner, A., Åslund, A., and Fischer, S. (1995). Economic reform and the process of global integration. Brookings papers on economic activity, 1995(1), 1-118.

Wacziarg, R., and Welch, K. H. (2008). Trade liberalization and growth: New evidence. The World Bank Economic Review, 22(2), 187-231.

United Nations. (2010). Economic liberalization and poverty reduction | United Nations iLibrary. Un-Ilibrary.org. https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789210545693c009

Comments