How has a narrow framing of mental illness within the criminal justice system impacted interventions

- Ethan Lobdell

- Nov 15, 2021

- 9 min read

Introduction

In the 1970’s the deinstitutionalization of individuals with mental illness hinged on the assumption that necessary social services would be available and accessible to these populations; these assumptions never materialized (Council of State Governments, 2002). In 2006, 64 percent of jail inmates, 56 percent of state prisoners, and 45 percent of federal prisoners experienced mental health problems compared to 11 percent of the general population (James & Glaze, 2006).

As the expectations of the criminal justice system(CJS) has expanded over the years, their interventions to improve outcomes for individuals with mental illness has seen varied success.

A Department of Justice study found a 75% recidivism rate for individuals with a mental health diagnosis compared to 43% for all released prisoners (Pew Center on the States, 2011). The opportunities for CJS to intervene are many. This paper seeks to demonstrate that mental health courts have minimal positive impacts on recidivism due to a narrow frame, neuroprediction needs to be applied within current procedural frameworks, prisons create negative feedback loops for individuals with mental illness, socioeconomic factors are the primary mediating factors for criminal behavior involving individuals who do not have late-onset mental illness, and recidivism as a metric needs re-evaluation. Collectively a narrow frame prioritizing the psychological causation narrative within these interventions minimize the effective evaluation of the complex dynamics that govern criminal justice outcomes for both individuals and society.

Factors contributing to recidivism of the mentally ill:

Mental Health Courts

One of the initial entry points into the criminal justice system is through the courts. Mental Health Courts were created to formalize procedural elements that address the specialized needs of mentally ill defendants. These courts have a dedicated judge, prosecutor, defense counsel, mental health treatment provider as well as multiple community service programs and treatment monitoring systems (Rossman, et al., 2012). Mental Health Courts are intended to characterize the psychiatric needs of individuals and connect them to appropriate services. Some have been shown to reduce recidivism and violence (McNiel and Binder, 2007). But a meta-analysis conducted in 2011 showed that Mental Health Courts have not been as effective as hoped for (Sarteschi, Vaugh, Kim, 2011). Sentencing/treatment recommendations often over-emphasize psychological factors which can lead to inappropriate interventions. From these recommendations, labeling and paternalistic bias from corrections officers and lower thresholds for technical violations often lead to re-arrest for technical violations - increasing recidivism and hampering offender support (Skeem, Manchek & Peterson, 2011). The narrow framing of these courts (prioritizing mental health) biases intervening agents towards a psychological frame which appears to limit the effectiveness of their interventions. Given that the court establishes the highest level of priorities within the CJS, it seems plausible that correction and probation officers would view their clients with a similarly narrow frame.

Neuroscience & prediction

Further exacerbating the narrow framing by the courts, the author reviewed the use of neuroscience and specifically, neuroprediction as an emergent tool in aiding sentencing and treatment recommendations (Aharoni et al., 2013). Traditional neuroscience risk assessments for recidivism use age, demographic, social, and psychological factors to support judicial decision making (Kiehl et al., 2018). Neuropredictiction proposes that neuroimaging can lead to improved recidivism predictions - benefiting society through the improved prediction of offenders who are more predisposed to future criminal behavior. The two primary ethical concerns associated with this technique are the loss of individual freedom from longer/harsher sentencing terms or the harm to society through an unjust and inadequate degree of accountability (Dunno, 2015). The effective integration of this technology within the court system is of significant importance to balance the collective benefit of minimizing the hypothetical risk an offender poses to society with the categorical importance of an individual’s due process and dignity. Current evidence suggests that neuroscience is effectively used in an objective way by the courts to adjudicate cases by incorporating evidence into the larger legal arguments (Denno, 2015). One hopes that the introduction of new technologies continue to be incorporated into the courts with a similar degree of objectivity and integrated application, to ensure outcomes reflect the ethical obligations the courts have to both individuals and society. And these tools risk further amplifying the psychological bias associated with Mental Health Courts by further emphasizing the role psychological factors play in the evaluation of a defendant.

Impact of solitary confinement on the incarceration loop

Once an offender has passed through the courts, one pathway forward through the CJS is the prison system. The percentage of individuals who experienced “serious psychological distress” during the first 30 days of incarceration was 26% compared to the average of 4% “serios psychological distress” within the general non-prison population (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2011). Prisons are not set up to effectively deal with large populations of mentally ill prisoners who are sensitive to the impact of psychological distress associated with prison life. One key tool in CSJ interventions is solitary confinement. Solitary confinement has been shown to trigger negative psychological reactions with mentally ill prisoners, escalating their diagnosis and elevating the likelihood of misconduct (Metzner & Fellner, 2013).

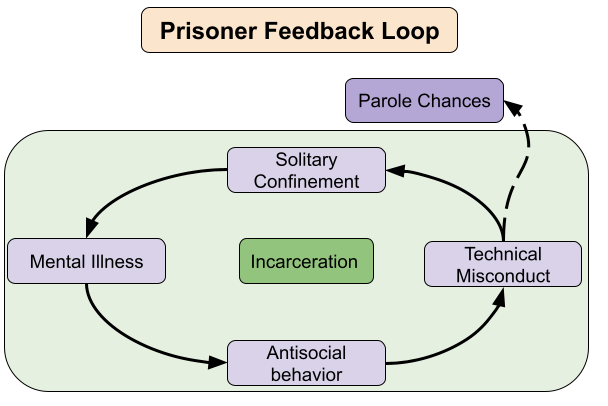

Figure 1.0: Negative feedback loop of incarceration

Fostering prosocial behavior is critical for inmates to move through this stage in the CSJ. If inmates have a prison track record of prosocial behavior they increase their chances of parole board approval. The problem lies in use of solitary confinement interventions in response to antisocial behavior, behavior that is frequently associated with mental illness. Solitary confinement often results in worsening mental illness which leads to more antisocial behavior, more infractions and more subsequent confinements and an overall reduction in the probability to achieve parole. This loop is significant because mentally ill inmates have high sensitivity to environmental conditions when trying to navigate traditional prison environments and hence exposes them to unfair treatment and minimizes the system's ability to foster their success.

Direct vs Mediated Effects on Criminal Behavior

The above evaluation of how mentally ill individuals interact with the CJS (courts & prisons) have historically been framed and critiqued under the belief that the deinstitutionalization of mental health treatment facilities led to the criminalization of mental illness and the subsequent incarceration of these individuals. A critical transformation that occurred within the past ten years identified that while the incarcerated population of offenders with mental illness increased, so too did their healthier counterparts, in part due to increased “tough on crime” public policies (Collier, 2014). This evidence challenged the deinstitutionalization hypothesis and exposed the need to better understand how mental health causes criminal behavior. Skeem, Manchek, and Peterson evaluated much of the contemporary research on criminology and mental health and revealed that mediating factors are much more closely correlated with criminal behavior than is associated directly with mental illness symptoms. While these mediated risk factors (antisocial behavior, homelessness, substance abuse, and criminal associates) are exacerbated by psychological factors, the direct effect of psychological factors does not appear to be the dominant risk factor for criminal behavior and recidivism. Although, psychological factors associated with late-stage onset can be used as an indicator for criminal behavior in older criminals. It is hypothesized that at older ages, psychological factors play a more dominant role in criminal behavior due to antisocial symptoms that emerge into typically stable socioeconomic conditions associated with that old age. Compare this to younger offenders, where mediated risk factors (social benefits, peer encouragement, personal values, and enjoyment from impulsive high-risk behavior (Bonta et al., 1998)) correlate more strongly for criminal behavior (Skeem et al., 2011). It is believed that this is due to mental illness and mediated risk factors co-evolving during younger years and greater benefits aligning with socially rewarded actions. The implications of these findings are to prioritize the contextual factors influencing criminal behavior of mental ill offenders of all ages. Distinguishing between the socioeconomic and psychological factors is key to improve the CJS’s outcomes and further evidence towards the hypothesis that narrow framing around psychological factors is over emphasized.

Recidivism as a metric

Lastly, it’s important to evaluate the utility of recidivism as a metric. One of the primary challenges associated with recidivism is that it is a binary metric attempting to quantify a dynamic process. The process an offender goes through to move from severity of and frequency of criminal behavior towards more prosocial behavior is complex. Prioritizing recidivism rates in evaluative systems does a disservice to both the individual offenders and the criminal justice system by obfuscating the specificity of an intervention's positive outcomes. Assuming the goal of the criminal justice system is “to advance public safety and promote proportional accountability for wrongdoing” (Hart, 1968) then we need metrics that demonstrate public safety is increasing and individual accountability to the rule of law is also increasing. With that purpose, recidivism is effective in measuring individuals who do not meet the desired outcomes. It is a metric with one guiding principle being simplicity and relative objectivity in measuring. But measuring the complement of a desired outcome is not necessarily measuring the desired outcome. For a complex outcome that has an arc of success that hinges on minimizing the frequency and severity of antisocial behavior, a more useful metric is necessary. Experts in the field have begun advocating for the use of desistance as a more accurate and appropriate metric. Desistance is modelled after success metrics found in the field of education. Desistance attempts to capture reductions in frequency or reductions in severity of re-arrests and to measure outcomes associated with prosocial behavior - not a trivial task. Desistance seeks to increase justice by valuing the direct relationship that should exist between a metric and its intended measurement goal. The critique of recidivism further supports the argument that how the Criminal Justice System frames the conversation and measures the actions of defendants does a disservice towards the overall goals of the system (Klingele, 2019).

Conclusion:

The dominant frame that mental illness has been criminalized and hence psychological factors should be prioritized to reduce recidivism has negatively impacted interventions. Current literature supports the limiting effects Mental Health Courts and solitary confinement have had in producing positive outcomes. Instead criminogenic behavior appears to be more strongly correlated to socioeconomic factors, particularly at younger ages while recognizing that psychological factors can predominate with late-stage mental illness onsets. And while psychological factors do increase the susceptibility for antisocial factors, the over prioritization of psychological treatment and stigmatization of mentally ill offenders is more likely to detract from the CJS outcomes of advancing public safety and increasing personal accountability to rule of law. As such this author recommends that a broad frame is utilized to more accurately identify the mediating causal factors at early stages in an individual's entry into the criminal justice system to inform the most appropriate interventions.

References:

Aharoni, E., Vincent, G. M., Harenski, C. L., Calhoun, V. D., Sinnott-Armstrong, W., Gazzaniga, M. S., & Kiehl, K. A. (2013). Neuroprediction of future rearrest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(15), 6223-6228.

Bonta, J., Law, M., & Hanson, C. (1998). The prediction of criminal and violent recidivism among mentally disordered offenders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 123, 123–142. Doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.123.2.123.

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2011-2012). Indicators of Mental Health Problems Reported by Prisoners and Jail Inmates

Council of State Governments. (2002). Criminal Justice / Mental Health Consensus Project Report. Lexington, KY: Council of State Governments.

Collier, Lorna. (2014) Incarceration Nation. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/10/incarceration

Ditton, M. (1999). Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report Mental Health and Treatment of Inmates and Probationers.

Denno, D. W. (2015). The myth of the double-edged sword: An empirical study of neuroscience evidence in criminal cases. BCL Rev., 56, 493.

HLA Hart, Prolegomenon to the Principles of Punishment, (1968). Punishment and Responsibility: Essays in the Philosophy of Law.

Houser, K. A., Vîlcică, E., Saum, C. A., & Hiller, M. L. (2019). Mental health risk factors and parole decisions: Does inmate mental health status affect who gets released. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(16), 2950.

James, D. J., & Glaze, L. E. (2006). Highlights mental health problems of prison and jail inmates.

Kiehl, K. A., Anderson, N. E., Aharoni, E., Maurer, J. M., Harenski, K. A., Rao, V., ... & Kosson, D. (2018). Age of gray matters: Neuroprediction of recidivism. NeuroImage: Clinical, 19, 813-823.

Klingele, C. (2019). Measuring Change: From Rates of Recidivism to Markets of Desistance. J. Crim. L. & Criminology, 109, 769.

McNiel, D. E., & Binder, R. L. (2007). Effectiveness of a mental health court in reducing criminal recidivism and violence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(9), 1395-1403.

Metzner, J. L., & Fellner, J. (2013). Solitary confinement and mental illness in US prisons: A challenge for medical ethics. Health and Human Rights in a Changing World, 316.

Pew Center on the States. (2011). State of Recidivism: The revolving Door of America’s Prisons

Rossman, S. B., Willison, J. B., Mallik-Kane, K., Kim, K., Debus-Sherrill, S., & Downey, P. M. (2012). Criminal justice interventions for offenders with mental illness: Evaluation of mental health courts in Bronx and Brooklyn, New York. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs.

Sarteschi, C. M., Vaughn, M. G., & Kim, K. (2011). Assessing the effectiveness of mental health courts: A quantitative review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(1), 12-20.

Skeem, J. L., Manchak, S., & Peterson, J. K. (2011). Correctional policy for offenders with mental illness: Creating a new paradigm for recidivism reduction. Law and human behavior, 35(2), 110-126.

Steadman, H. J., Osher, F. C., Robbins, P. C., Case, B., & Samuels, S. (2009). Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatric services, 60(6), 761-765.

Comments