What do the 2019 Chilean protests reveal about the dynamics of Chile’s macroeconomic success?

- Ethan Lobdell

- Nov 15, 2021

- 8 min read

Updated: Jan 25, 2022

Background:

Since the fall of 2019, Chilean citizens have engaged in violent and non-violent protests in response to grievances regarding economic and social conditions. A $0.04 price increase in metro fares, on October 1st, 2019, led to non-violent protests by high school students. These protests grew in size to approximately 3.7 million citizens of all ages through both violent and non-violent means (Europa, 2019).

The demands of the protestors are a reversal of public transport fares, reforms in education, healthcare, and pension systems, better wages, minimum wage increases, the resignation of President Sebastián Piñera, a new constitution, and the formation of a new government (2019-2020 Chilean protests, 2020). These demands come after Chile (only Latin American member of the OECD) has experienced the most significant economic growth of any Latin American country over the past several decades (OECD, 2010). This author seeks to explore the following explanatory challenge:

What do the 2019-2020 Chilean protests reveal about the complex dynamics of Chile’s macroeconomic success and subsequent social and economic inequality?

Exogenous & Endogenous Landscape

While conventional indicators show a significant decline in inequality, the perception among Chile’s citizens is that inequality has greatly increased. The development model Chile followed since the 1980s was successful in generating growth and reducing poverty. But it did not function properly in a middle-income country (Edwards, 2019).

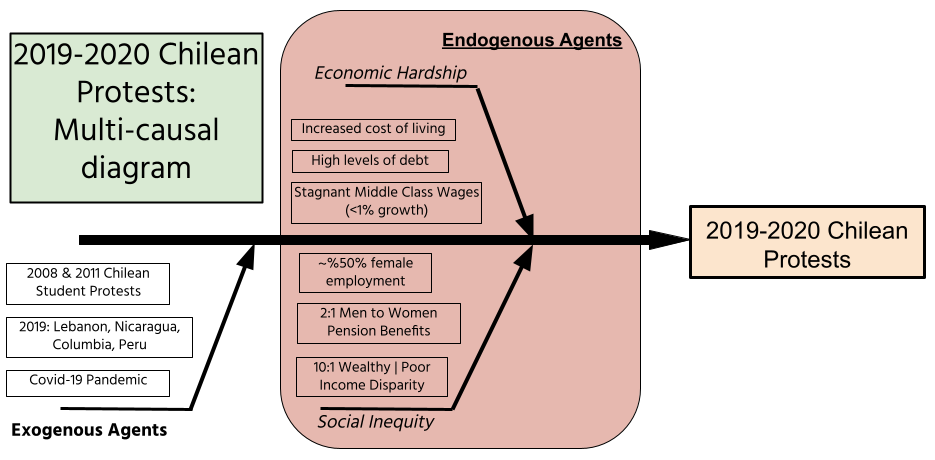

The two most salient domains of analysis of the 2019-2020 Chilean protests are the endogenous factors ( economic, political and social) and the exogenous factors (pandemics, global instability, and international agents).

Image 1.0: Fishbone diagram outlines the sub-causes under both the endogenous & exogenous lenses that are linked to the 2019-2020 protests.

Endogenous Agents:

The Chilean unrest that has unfolded since October of 2019, has exposed the significant dissatisfaction, among the Chilean middle class, with the current social, political, and economic systems. This dissatisfaction comes despite significant macroeconomic gains that Chile has experienced through its neoliberal economic policies initiated by General Augusto Pinochet's regime in the early 1980’s. Pinochet and Chile’s system of economic policy was influenced by the “Chicago Boys”, a group of Chilean economists trained in libertarian economic theory as taught at the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman. Their influences led to significant macro-economic improvements for Chile as indicated by multiple metrics in Table 1.0 (Collins and Lear 1991).

Table 1.0: Macroeconomic indicators of significant macro-economic improvement. (World Bank Development Research Group, 2020)

Free market economics moved Chile towards privatization of nearly all major industries. The impact of privatization of education, healthcare and the pension system reveals inequalities that have had a significant impact on Chilean society.

Chile’s higher education systems are 85% private owned (Ministry of Education, 2010). Many families incur significant debt to support university attendance (Americas Quarterly, 2012). Chile has also experienced a decrease in public school attendance from 80% in 1973 to 40% in 2014. Since funding is related to enrollment, significant decreases in enrollment have left public schools with limited resources (Santiago, 2017).

Privatization of the Chilean pension system has had a positive effect on the macro level through the freedom to invest public pensions in competitive markets and attract multinational financial institutions into the Chilean economic system (Williams, 2001). The private pension system has benefited high wage male workers, who receive on average $1000/month compared to $500/month for low-wage and/or female workers (Vasquez, 2016).

An unequal distribution of resources and delivery of service exists between the public (FONASA) and private(ISAPREs) health-care systems (Aguilera, 2014). 47% of health care spending is spent on 17% of the population (Public tensions, private woes, 2011).

In summary, the endogenous agents are all linked through challenges associated with equity during Chile’s migration to a free-market society. Chile has seen positive socio-economic benefits to both its education system, pension system, and healthcare system at the macro level. But these benefits have primarily favored the top 20% of income earners due to accelerated mobility associated with agency. The challenge lies in that high levels of debt, limits to pension benefits, difficulty accessing quality education, and difficulty accessing quality healthcare are all obstacles for lower and middle class citizens with limited agency. And while these agents are not necessary for social unrest they are sufficient to cause unrest - given they may trigger emotional states that may be necessary for unrest. These competing narratives have led to strained societal cohesion between the top 20% of income earners and the rest of society. The explicit inequity in improvements drives the social tension. Inequity is captured best by the fact that the top 20% of Chilean households have 10.3 times (highest of all OECD nations) the income of the lowest 20% of households (OECD, 2020).

Exogenous Agents:

This paper explores two exogenous agents that influence the 2019-2020 protests. The first is the Covid-19 pandemic and the second is destabilizing international events. The Covid-19 pandemic has introduced a significant negative feedback loop into Chilean and international society. The pandemic began within months of the initial equilibrium state that was achieved between protestors and the government in November 2019. The ensuing lock-downs impacted markets, with one assessment forecasting an economic contraction between 1.5% and 2.5% in 2020. Given that 53% of Chilean residents are at risk of falling into poverty if they lack income for more than 3 months, the current lock-downs are amplifying economic hardships of many citizens and driving protestors back to the streets for change (OECD, 2020).

There were many destabilizing international events in 2019. Lebanon, Nicaragua, Peru, Columbia, Hong Kong, India, Spain, France, and Sudan have all been experiencing social unrest associated with economic inequality and agency (Nugent, 2020). Protesting agents have opportunities to find cohesion and motivation around similar social movements despite geographic divides (Gonzales, 2016). Given that only 85% of Chileans feel supported compared to an OECD average of 89% (OECD Better Life Index, 2020), solidarity across nations could be a key motivator due to a desire to connect.

Networks & Dynamics:

The destabilizing international event agent is activated via modern communication networks. These networks create opportunities for agents to primarily address logistical challenges, secondarily share emotional solidarity, and lastly to orient ideologically (Jost, et al., 2018). These effects map well onto a small-world network model due to the distance between nodes within country clusters and the density of these clusters ~ 3.7million protestors within Santiago. The networks demonstrate robustness due to the decentralized nature of the movement and a high sensitivity to non-linear growth. Current research suggests that while the potential for network effects is possible, evidence points to the difficulty those effects have in crossing international borders through social media (Gonzales, 2016). As such this author views communication networks as a sufficient causal mechanism for social unrest but not a necessary one.

One key node within our network is the individual. Their motivation for change is to improve agency with their personal health (Sherwood, 2020). And yet through the decentralized network, individuals may participate in protests, during the Covid-19 pandemic, that risk both virus infection and physical harm. This risk seeking behavior emerges from an individual's effort to promote their self-interest to a re-prioritization of the collective goals of social change. Risking individual harm to benefit the collective through violent protest has been seen when trust, density and diversity is high within social networks (Loveman, 1998). Very few individuals seeking to improve their personal health and stability would willinging destroy state property, had there not been a motivating belief in the power and safety of the collective. This behavior requires that a certain threshold of individuals respond to the behavior of the group and elevate their risk tolerance (Granovetter, 1978).

Equilibrium States:

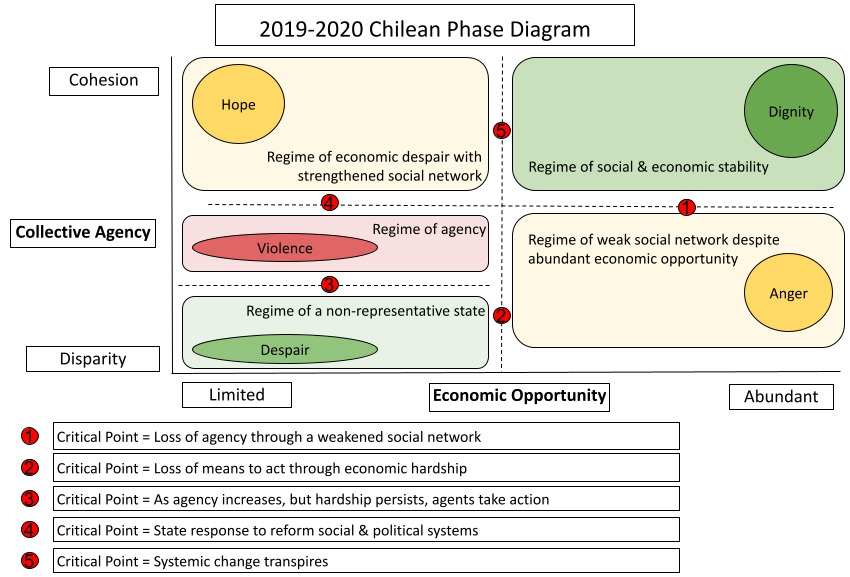

Image 2.0: The Chilean phase diagram reveals five regimes with five attractor states for an individual or cluster of individuals. The critical points reflect changes within the perception of economic opportunity and agency within a socio-political system.

The inequity of economic and social experiences of the different income groups of Chilean society compels this author to use collective agency and economic opportunity to define the dimensions of our phase diagram. There is compelling evidence to support that emotions provide the power to motivate the ideas of our agents. Collective behavior is relatively stable in those emotional states. We explore one pathway through the phase space: agents start with dignity, are pushed into anger, then despair, through violence, into hope and then back to dignity (Jasper, 1998). In the case of Chile, through the initial privatization efforts, many Chileans moved out of poverty or experienced a general improvement in their social and economic life - a dignifying experience. As privatization accelerated the agency of fewer and fewer citizens, the Chilean middle class grew angry and protested the inequality (education protests of 2008 and 2011). As time evolved, privatized industries segregated by income bracket and quality services that many Chileans desired could not be afforded or accessed. So while individual metrics showed growing incomes, purchasing power for the middle class declined and this provoked a sense of despair and fear of descent into poverty for many middle class Chileans. But, as communication networks (social media) bonded individual agents around these emotional states and shared grievances, collective agency evolved into violent and nonviolent protests (i.e, October 2019). As the Chilean government responded to protestor demands (improvements in healthcare, education, pensions and a referendum on the Constitution), hope arose and stabilized the system. If the changes enacted address the concerns of the people, dignity has an opportunity to be restored - something many Chileans explicitly desire (Edwards, 2019). But other pathways could emerge (i.e. back to violence due to external noise such as the Covid-19 pandemic or lack of follow through from the state).

Discussion:

This author finds that different rates of economic growth and agency associated with the privatization of Chilean institutions led to significant real and perceived inequities between various economic classes within Chilean society. These inequities pushed Chilean society into a sensitive phase state that was responsive to both endogenous and exogenous mechanisms. And despite the social dissolution associated with a privatized society, emotional bonds between individual agents forged through common history and shared experiences were amplified through international and local communication networks to form a decentralized movement for societal change. The outcome of which resulted in the Chilean state agreeing to reform the nation's constitution and its healthcare, education, and pension systems in response to the emergent decentralized behavior of millions of citizens.

References:

2019-2020 Chilean protests. (2020, May 27). In Wikipedia. Retrieved May 30, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2019%E2%80%932020_Chilean_protests

Aguilera, X., Castillo-Laborde, C., Najera-De Ferrari, M., Delgado, I., & Ibañez, C. (2014). Monitoring and evaluating progress towards universal health coverage in Chile. PLoS medicine, 11(9).

Aguilar, J. (2020, April 20). Chile Special April 2020. Retrieved June 01, 2020, from https://www.focus-economics.com/countries/chile/news/special/government-unveils-ambitious-stimulus-to-contain-the-impact-of-covid-19

Americas Quarterly. (2012, November 06). Higher Education in Chile. Retrieved May 31, 2020, from https://www.americasquarterly.org/higher-education-in-chile/

Braha, D. (2012). Global civil unrest: contagion, self-organization, and prediction. PloS one, 7(10).

Chile Poverty Rate 1987-2020. (n.d.). Retrieved May 30, 2020, from https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/CHL/chile/poverty-rate

Collins, J., & Lear, J. (1991, May). Pinchet's Giveaway. Retrieved from https://www.multinationalmonitor.org/hyper/issues/1991/05/collins.html

Edwards, S. (2019, November 19). The Reality of Inequality and Its Perception: Chile's Paradox Explained. Retrieved May 31, 2020, from https://promarket.org/2019/11/19/the-reality-of-inequality-and-its-perception-chiles-paradox-explained/

Europa Press. (2019, November 13). Las autoridades chilenas estiman que 3,7 millones de personas participaron en alguna de las protestas. Retrieved May 30, 2020, from https://www.europapress.es/internacional/noticia-autoridades-chilenas-estiman-37-millones-personas-participaron-alguna-protestas-20191113132053.html

French, G. (2014, December 20). Summary of Issues for the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Pre-Session on Chile (2014) - GI-ESCR. Retrieved May 31, 2020, from https://www.gi-escr.org/publications/summary-of-issues-for-the-un-committee-on-economic-social-and-cultural-rights-pre-session-on-chile-december-2014-1

Granovetter, M. (1978). Threshold models of collective behavior. American Journal of Sociology. 1420-1443. Available through Claremont Libraries, Journal: American Journal of Sociology, Database: JSTOR Arts & Sciences I Collection Coverage:(1895-07-01~4 years ago, volume:1;issue:1)

González-Bailón, S., & Wang, N. (2016). Networked discontent: The anatomy of protest campaigns in social media. Social networks, 44, 95-104.

Jasper, J. (1998). The Emotions of Protest: Affective and Reactive Emotions in and around Social Movements. Sociological Forum, 13(3), 397-424. Retrieved June 3, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/684696

Jost, J. T., Barberá, P., Bonneau, R., Langer, M., Metzger, M., Nagler, J., ... & Tucker, J. A. (2018). How social media facilitates political protest: Information, motivation, and social networks. Political psychology, 39, 85-118.

Loveman, M. (1998). High‐Risk Collective Action: Defending Human Rights in Chile, Uruguay, and Argentina. American Journal of Sociology, 104(2), 477-525. doi:10.1086/210045

Ministry of Education of Chile. (2013). "BASES DE DATOS DE MATRICULADOS". mifuturo.cl. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

Nugent, C. (2020, January 16). Why the "Surge" of Protests in 2019 will Continue in 2020. Retrieved June 01, 2020, from https://time.com/5766422/protests-unrest-2019-2020/

OECD. (2010, January 11). Chile signs up as first OECD member in South America. Retrieved May, 2020 from https://www.oecd.org/chile/chilesignsupasfirstoecdmemberinsouthamerica.htm

OECD (2019), Under Pressure: The Squeezed Middle Class, [Figure 4.5]

OECD. (2020, March 9). How's Life? 2020: Measuring Well-being. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/how-s-life/volume-/issue-_9870c393-en

Public tensions, private woes in Chile. (2011, March 04). Retrieved June 02, 2020, from https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/11/08-031108/en/

Santiago, Paulo, et al. (2017), “Funding of school education in Chile”, in OECD Reviews of School Resources: Chile 2017, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Sherwood, D. (2020, January 05). Chile's president sends Congress plan to slash health care costs after protests. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-chile-protests/chiles-president-sends-congress-plan-to-slash-health-care-costs-after-protests-idUSKBN1Z40QN

Vasquez, I. (2016, August 16). The Attack on Chile's Private Pension System. Retrieved from https://www.cato.org/blog/attack-chiles-private-pension-system

Williamson, J. B. (2001). Privatizing public pension systems: Lessons from Latin America. Journal of Aging Studies, 15(3), 285-302.

World Bank Development Research Group. (2020). GINI index (World Bank Estimate) - Chile. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI?contextual=default

Comments